THE MEANING MAZE

THE MUTILATION OF MEANING

After an initial period of growing concern, doubt and uncertainty, events that they could not ignore led them to the demanding need for decisions about how to respond. Events were changing the meanings of actions and communications within their culture, and their decisions indicated their understanding of these cultural shifts.

The intensely painful emotions and thoughts converging on these decisions are not adequately rendered by sentences on a printed page. Each individual within the German resistance remained someone with private concerns, pleasures, problems, and family members to care for. The search for daily happiness and pleasure did not disappear with the advent of their pursuit of an honorable government for Germany. Yet, somehow decades later the texture of their daily lives and concerns is easily lost in the fog of our focus on what “ought to be done” and our bitter recollection of Nazi atrocities. It is easy to fail to understand how imminent, grave danger made every action to preserve honor in the midst of Nazi despotism so formidable a decision for each in the German resistance.

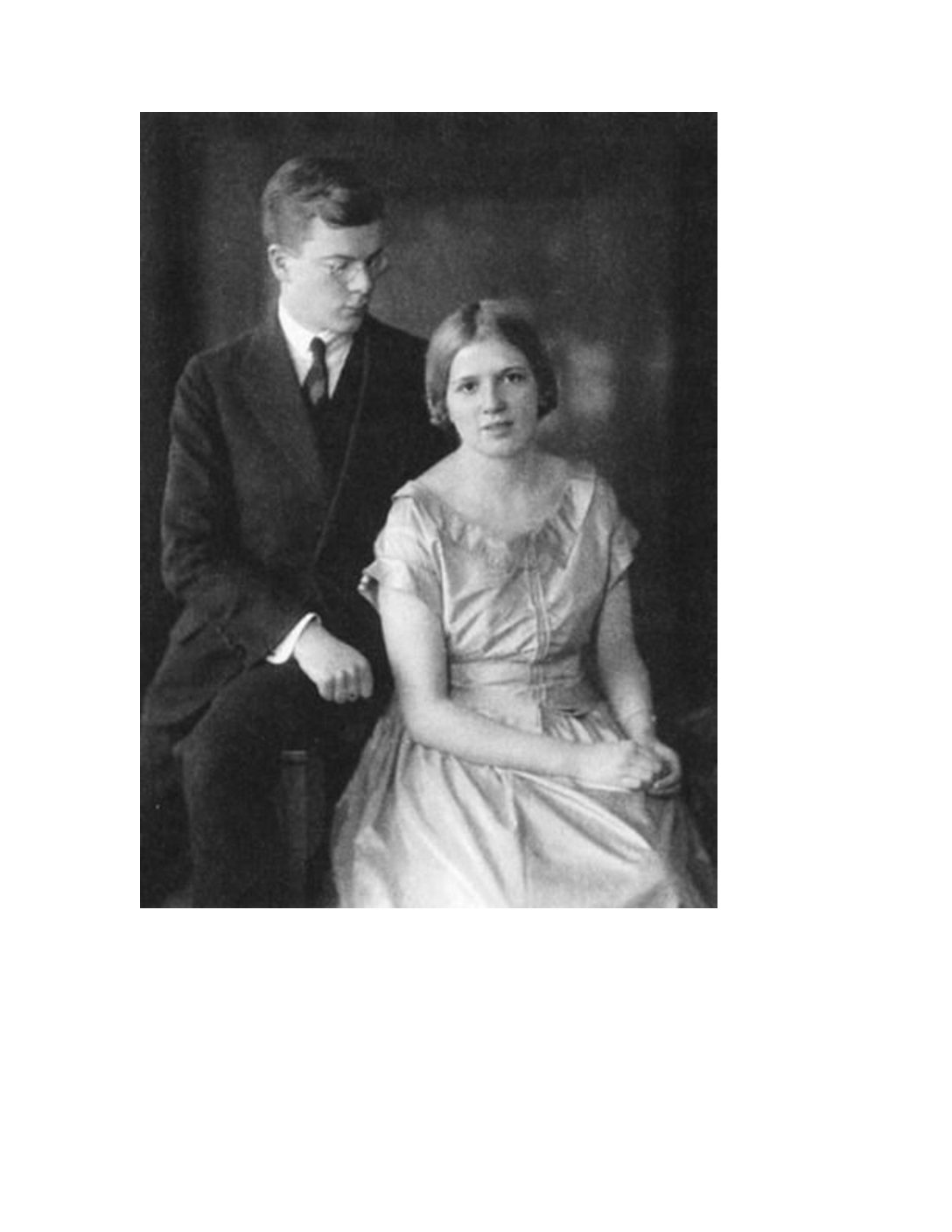

By then, some in the family were already engaged in the most audacious form of opposition: working in public office as a cover for subversive activity against the state. Hans von Dohnanyi was shouldering this dual burden, his vulnerability on account of his racial “stigma” notwithstanding, and so was Rüdiger Schleicher, in the legal department of Hermann Göring’s Air Ministry. (Despite his deepest misgivings, he joined the Nazi Party in order to keep his position — and its subversive possibilities.) There was also Klaus Bonhoeffer, by 1935 a chief lawyer for Lufthansa, a position that permitted him to take trips abroad that he then could use for clandestine resistance purposes, and Klaus’s brother-in-law Justus Delbrück, who was soon to join the active resistance.

All these men and their families had by now become adepts of secretive communication — writing with ciphers, speaking on the telephone in agreed-upon codes, hiding messages — daily practices of camouflage and dissimulation that anti-Nazis had to adopt if they wished to get on with life. Hans became well practiced in using ironic exaggeration to convey his impressions of what was going on. Soon, some among them had to take it further: they had to plan how they would keep in touch were they to be arrested and jailed. The Bonhoeffers decided how they would use books delivered to prisoners as message devices, putting tiny dots under letters spread out over many pages that together spelled out instructions, warnings, news, or loving notes of support; they learned how to write in minuscule script on tiny bits of paper or cardboard that could be buried at the bottom of a jar of food or hidden in a bunch of flowers; they trained themselves to speak to each other in the presence of police or other officers without giving anything away. Among people who to the core of their being valued honesty and truth, these techniques, which only the most urgent crisis permitted, aroused a sometimes comic spirit and at other times moral repugnance. . . .

Hitler’s defiance and deception of the West was continuing apace. In March 1936 he had announced, in a dramatic speech to the Nazified Reichstag, that at that very moment German troops were re-entering the Rhineland, which had been demilitarized under the Versailles Treaty. This breach of the established order had been followed instantly by pious plans for European peace. But Hitler divulged his real intentions in a confidential talk with his six principal military chiefs on November 5, 1937, in which he outlined his plans for war and a New Order in Europe.

When Hans von Dohnanyi heard about this, he instantly understood its importance and conferred at once with like-minded opponents of the regime. More than a few Wehrmacht officers were shocked by the irresponsibility of Hitler’s plans. How could this march to war be stopped? Was there any other option but the removal of Hitler? They could not see one. And if that was the only solution, by what means would it be achieved? Obviously their conversations required discretion and secrecy in carefully camouflaged settings, for there was surveillance everywhere, safety nowhere.

Hitler was also manipulating a new crisis within the military leadership, for both his minister of war, Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, and his army commander in chief, General Werner von Fritsch, were opposed to his war plans. These officers would have to be purged, and Hitler dealt with them by exploiting a sordid calamity in the first case and falsifying records in the second. The widowed Blomberg had impulsively decided to marry a rather common woman thirty-five years his junior and Hitler had happily agreed to be a witness at the wedding (Göring was best man) in early January 1938 — only to learn soon after that the new wife was very common indeed: in 1932 sh had posed for pornographic pictures taken by a Jew with whom she was then living and had been arrested; in 1933 the policed registered her as a prostitute. So Blomberg had to go. And the Gestapo blackmailed his likely successor, the very popular, well-regarded General Fritsch, on a trumped-up charge about an alleged homosexual relationship some years earlier. He too had to go.

Dohnanyi was sickened by the baseness of these illegal maneuvers, disgusted by Fritsch’s removal, and troubled by the new army structure Hitler invented, with a Supreme High Command of the Armed Forces under Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, a spineless officer who was totally subservient to the Fürer and consumed by his own vanity. Dohnanyi continued his contacts with some of the disaffected officers.

Elizabeth Sifton and Fritz Stern (2013). No Ordinary Men: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Hans von Dohnányi, Resisters Against Hitler in Church and State. New York: New York Review Books, pp. 53 – ??

Accompanying music:

Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 6 in F, 2. Andante molto mosso

Christoph von Dohnányi, The Cleveland Orchestra & Chorus, Telarc Digital